It’s commonly understood that when visiting Florence you must to go to the Galleria dell’Accademia and see Michelangelo’s David.

And indeed, you probably should, if only for the museum itself and its Botticellis and Giambolognas and Giottos. But you certainly don’t have to go there to see David and in fact you don’t even have to go there to see Michelangelo’s David.

The famous giant-killer of the old testament has long been claimed by the city to symbolise its reputation for resistance to foreign authority. There are representations of David all over the city including statues by Donatello and Verrocchio and paintings and the inevitable little plaster copies that you can buy to take home and regret, unlike the calendars and postcards and barbeque aprons.

There are even copies of Michelangelo’s David in full view if you decide to take in a bit of this deeply historic renaissance city instead of waiting in line at the Galleria and visit, say the thousand year old Ponte Vecchio and its still operational market stalls, or the Pitti Palace, seat of the powerful Medici family with its resplendent statuary-filled Boboli gardens, or just have a bite of pizza. Along the way you might spot the full-size replica of David in front of Palazzo Vecchio or the bronze copy at Piazzale Michelangelo while taking in its expansive view of the city.

Having said that there’s probably good reason why the David you have to wait in line to see is the single most famous statue in the world. This fame dates to its troubled past, which began in 1464, eleven years before the birth of Michelangelo, in a marble quarry 100km from the city. City guildsman commissioned the extraction of this particularly massive and fragile slab of marble as the raw material of their tribute to the Basilica, which would be a five metre David perched high in the buttresses.

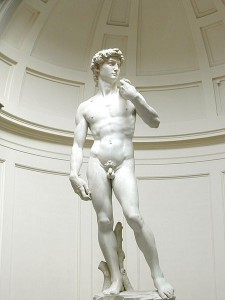

The slab was problematic from the start. First it was huge and demanded a correspondingly huge and seamless David. Also it was intimidatingly valuable and capable of destroying the most solid reputations. Finally it had an awkward narrowness about the middle of just a little over half a metre, requiring a clever posing of the hero king.

The marble bested two sculptors before Michelangelo was given his career-making opportunity by a committee that included Leonardo da Vinci in 1501. At 27 and with the benefit of youthful arrogance, Michelangelo addressed the problems posed by the slab by breaking all the rules. Previous Davids had been peasant kings and warriors, resolute and aggressive, but Michelangelo’s David was passive and tranquil and, possibly to avoid wasting scarce girth, naked.

The reposing posture and sheer size presented one final challenge — David wouldn’t stand up on his own. So Michelangelo conceded a single prop, in addition to the deadly sling cast casually over the king’s shoulder, in the form of a small tree stump fused to the right leg.

Together it all looks very casual and certainly familiar but when it was unveiled Michelangelo’s David was a revolution in sculpture. Seen with this in mind the lineups and imitation become more easily understood. Yet even then this extraordinary David is only one of many Davids and one of many amazing things to see in Florence.